Tituba’s Daughter

It’s Halloween time, that magical time of the year when historically, pre-Roman Europeans celebrated the Fall Harvest, a time of plenty, with seasonal pagan festivities that became syncretic after Roman conquest, and, according to many cultures across the world, a time when the veil between the supernatural and the human world is at its thinnest, and ghouls, demons, and ghosts roam this corporeal realm.

It’s also the time for hundreds of white women thinkpieces about the empowering (European) feminist history of witches and their place in (European) society.

Clever insight on how the (European) demonization and persecution of accused (European) witches and paganism was actually mired in misogyny and the fear of female thinkers, healers, and midwives, and how (white) suburban sleepover games of “Light as a feather, stiff as a board” operated as early girlhood forms of female empowerment and sexual, often sapphic, awakening will abound, along with women everywhere laying feminist claim to the legacy of the Salem Witch Trials and the townspeople persecuted. This interpretation of history lead to modern (white) feminist depictions of hip alt girl covens and (white) pagan witchcraft. However, the very important aforementioned bits in parentheses are, funny enough, more often than not omitted.

Over the years, I came to an understanding of the intentional nature of that whiteness and my own Witchy-ness despite its dominance in mainstream lore and media.

As a child, I loved the magical, witchy girls I saw on TV. Lydia of “Beetle-juice”, Sabrina the Teenage Witch, the Sailor Scouts, Matilda. Any witch I could get a hold of and past my superstitious but Calvinist West Indian parents. I dreamed of a day when I could magic my way out of my shitty home just like Roald Dahl’s famous little girl witch and be done with my abusive chaotic family life. It was with his story of a little girl with magical powers finding a way to succeed against horribly inept and cruel adults that I found a familiar and first became acquainted with the idea of life outside of my parents’ chaotic and violent home and chosen family through magic. My superstitious West Indian parents were adamantly opposed to any shows, movies, and even cartoons about the supernatural, so I had to sneak watching these things.

When I was in the 2nd grade, the white girl that bullied me and would eventually threaten to shoot me for being Black often teased me for “looking like a witch” because ofmy big hair, big dark eyes, and quiet reserved demeanor. It wasn’t something new to me, having been teased by my brother for the same thing. But I hated it beyond belief. I had been reduced to tears the first time my brother called me a “bruja”. But this girl’s accusation was weird, she’d bully and tease me for being a witch, then sometimes challenge my know-how and witchy powers boasting her own and threatening me with her ability, or with telling on me for practicing witchcraft. I often denied any witch affiliations, but like her, would competitively often flip flop and engage, telling stories of stones and crystals I’d found and their powers.

Once, when my bully was building towers with blocks and I looked over at her. The blocks fell. She jeered meanly “Stop that!”. After the third or fourth time, she actually became afraid. I knew from the beginning I wasn’t causing the bricks to fall, but after a while, even I started to question if I had some latent abilities.

But I’d realized it didn’t matter that I wasn’t actually making shit happened. That little asshole was now terrified of me. She backed off with racially harassing and intimidating me for almost a whole week.

As a baby goth, I got enraptured by the movie version of “The Crucible” and the story of the Salem witch trials during my high school years in the early aughts. With appreciation and newly-discovered love for theater in tow, I tried out for my high school’s production of the play during my sophomore or junior year. The drama teacher in charge of the production was adamant about the fact that those who didn’t come to try out could not be in the play. No exceptions, no questions asked. I was excited at the prospect of being cast. I was ambitiously gunning for the lead role of Abigail Williams.

When it was my turn to audition, the teacher (who will remain unnamed as he still works at my old high school) asked me where I was from. A bit confused but enthusiastic, I said “I’m Dominican.”

He continued enthusiastically. “So you can do Island accents?”

“Oh, uh, yeah, of course!” I said, becoming less sure but wanting to prove my ability. I mean, that’s what acting is about, right, having multifaceted and diverse acting skills, being able to switch between characters seamlessly.

“Great” he responded, and without skipping a beat, followed “OK, read for Tituba? Be enthusiastic and speak with something like a Jamaican accent”?

Tituba??? I panicked. She was depicted as heavy set and Black, two things which I always hated having been born into a family of lighter-skinned, passing, thin Creole Dominicans.

Embarrassed and confused at being so blatantly type-casted in a room filled with other students trying out, I bombed the audition fantastically. The one thing that my shy, anxious high school-self felt finally confidence doing suddenly became anxiety-inducing and terrifying like everything else in my life generally was.

A pretty, thin white girl who was popular in the theater department and hadn’t come to formal auditions for the play got the role of Abigail, despite the rule of “No audition, no play” decree firmly expressed beforehand.

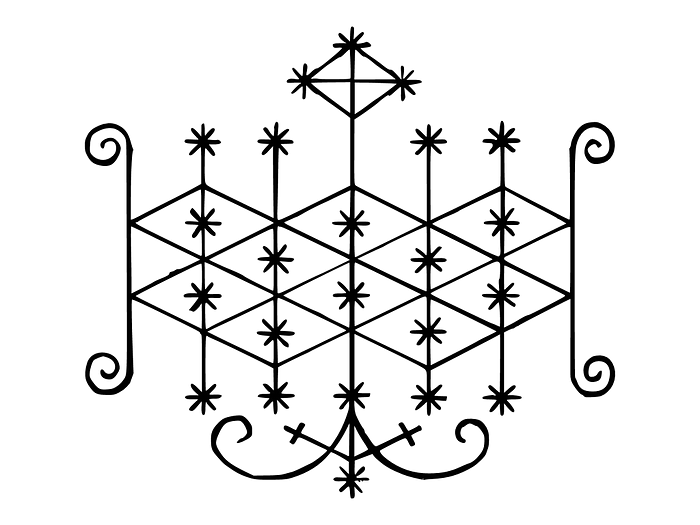

Two years back, I went digging for information about American Witchcraft and the history of Salem to find out about Tituba. Since my initial introduction to her as the caricature mammy side-character to the bevy of persecuted colonial New England girls, I’d come to understand that I had been greatly mislead and Voodoo was intentionally misrepresented by scared racist Europeans, who had policed and banned practice of Afro-diasporic spirituality across the colonies in the “New World” so as to squelch the fires of slave rebellions and uprisings eventually stoked by the likes of Creoles like Marie Laveau and Mary Ellen Pleasant, and to force assimilation of the slaves who yet strongly held onto their West African heritage through their religious practice.

In the books I got from the library during my research, depictions and tales of the Salem witch trials and their legacy were heavily featured, the persecuted European female citizens of Salem town focused in great detail. But Tituba, the Voodoo-practicing slave woman at the heart of the debacle, is shrouded in mystery. Surprisingly, it was documented that she was not persecuted during the trials, and was merely shipped back to what many believe was her home in Barbados, though that was rife with its own negative implications. And that’s the end of that. There’s conflicting details on her racial identity (though it is generally assumed she was a mixed woman of West Indian descent) and not much information on what came of her after that. The larger legacy of the trials do not include her much at all, much less focus on her as a central character. The descendants of Salem and the tragedies that happened there are seen solely as the European descendants of the persecuted. Thus, media depictions of great female witches that come from the Salem line are always white.

But how could the white girls who were allegedly being found being taught Voodoo by the West Indian slave woman and were purported to be unfairly persecuted for it for their proximity to un-Christian Blackness despite being innocent be the magical descendants to that legacy? Would such a title belong to West Indian girls and others descendants of the diaspora, the people who suffered most the violence of persecution and forced assimilation and erasure of their spiritual cultures and identities as part of the dehumanizing violence of European slavery?

According to my mother, her and her twin brother were born to a widow thanks to a demon. That is, there is a spirit that haunts the family. This is something that has been confirmed by other members of her family. It has brought much misfortune and chaos and has possessed various different members of the family, including causing her father’s death. Her father, as it were, was an exorcist. He was once doing an exorcism of a demon on a cousin of my mother’s. In the midst of the exorcism, right as the demon was about to be expelled from the girl’s body, she crowed “I will break your neck.” As the story goes, two months later, he died of a freak accident while jumping down from a truck or something mundane like that, his neck twisted at an unnatural angle. At his funeral, that cousin who he had exorcised was in attendance and acting normally, mourning, until she sudden became possessed again and started to laugh hysterically. “See?? I told you, I told you I’d break your neck!” Word has it that after that, everything became weirdly calm as the family started to convert to Christianity. And, for one reason or another, the demon was said to have feared my mother and her brother. “The twins, the twins cannot be touched!” one possessed family member is purported to have said.

It is stories like this she tells me any time I get the courage to ask her anything about Voodoo, Los 21 Divisones, Santeria, etc in the Dominican Republic. She admonishes me for the gris gris I wear around my neck and tells me that they are not things to take lightly. I was kept from sleepovers where white girls play Bloody Mary and with Ouiji for that reason too. Such is the fear of diasporic African spirituality among those in the Afro-Latinx diaspora. I wonder how many more violent manifestations of the Salem witch trials must have happened across the Islands to so thoroughly impart such a fear and stigma around diasporic spirituality even centuries later.

At 17, I had one huge, long, manic break down when I came to terms with the fact that I didn’t believe in Heaven or Hell. It was after a rather traumatizing stint at a Youth Retreat at my (parents’) church. I couldn’t sleep without having full on panic attacks brought on by visions of death, of no afterlife, of Hell, of damnation, of a Christian God turning his back on me, on me turning my back on a Christian God.

Last year, when I was in the middle of yet another sleepless, teary, depressive breakdown, calmly reflecting and meditating and listening to Ibeyi over my altar brought me a level of peace and calm and control over my life when everything was spinning marvelously out of control. It did that by reminding me who I am, where I come from, of my roots, of my spirit. A good friend and fellow Afro-Dominican spiritualista gave me a stick of palo santo. The smell of it burning brings me a small sense of sadness and peace. I couldn’t exactly settle these practices with my atheism. I still really can’t. All I know is that for me, it all somehow makes sense and it makes me feel more at ease and closer to something I can’t exactly describe or explain too well, but feels very intimate to me.

Both then and now, have more in common with Tituba, the embattled enslaved mixed woman of questionable Indigenous and African ancestry resisting against the white powers that be with every cultural resource she had access to than I do with Goody Williams or any of her current-day fey Anglo-American pagan equivalents.

Being a witch is about something more than having being quiet and obsessed with cats as a kid, or a depressive and angsty and goth as a teen. It goes well beyond being a strong-willed, intelligent, woman-identified woman whose power threatens the patriarchal status quo, or having always being a ritual little girl with a love of stones and rings and trinkets who believes in sixth senses, magic, and intuition, or being extremely gay. It’s about how people perceive me and treat me as a mixed Latina, and my people’s social position and identity in opposition to whiteness, then and now. It is my spoken and unspoken roots, my history, the stories and traditions and rules I was raised with and that were passed down and the ways I reject the stigma to find a connection to a self that is faithful to my past and present.

To me, there is no greater power than that.